ChatGPT in the English Classroom: 18 Students Test it and Share their Insights

Nancy J. Murray, MFA

From the English Department, School of Writing, Literacy and Languages, Community College of Baltimore County, Baltimore, Maryland.

Nancy J. Murray, MFA

nmurray@ccbcmd.edu

ABSTRACT

18 students engaged in learning about artificial intelligence, specifically ChatGPT 3 (CHAT), to respond to the question of whether it is ethical or practical for students to use CHAT in college-level classrooms to complete assignments. A thematic unit was created and taught in 2 face-to-face English 101 classes to explore the topic of CHAT. The unit was created with and designed to be completed by CHAT. After reflecting on 3 readings, 2 videos, and completing various related assignments, students were expected to write a 5-page essay about CHAT using CHAT in whatever way they wanted to complete the work while still maintaining the specific requirements of the English 101 objectives. The essays were examined by the students using the same peer review process that we used for 2 essays written without using CHAT before the thematic unit, with the addition of 2 instructions: to check the veracity of the sources, and to evaluate the essays for consistency of tone, accuracy of information, and originality. Data collection for this qualitative study was based on hand-written reflections by 18 of the students in the classroom, quick polls at the end of each lesson, and semi-structured, recorded interviews with 9 of the participating students who volunteered to be recorded. The students were charged with the dual roles of tester and consultant, and it gave them the opportunity to understand and test CHAT in a classroom and to share their insights with faculty. Reflections and interviews were transcribed, coded, analyzed, and categorized into the 3 strongest recommendations for faculty considering using CHAT in their curriculum: (1) faculty should be open-minded and well trained in what CHAT is and how to use it safely before attempting to allow their students to use it in class; (2) students should be given specific instructions for how to use CHAT for specific tasks that will help them reach their potential and then allowed to decide for themselves how to proceed; (3) students should be tested to demonstrate comprehension of the material and classroom objectives both before and after the use of CHAT.

INTRODUCTION

We were at the tail end of the fall 2021 semester in an English 101 class when my student confessed to writing his essay using artificial intelligence (AI) and asked if I thought it was cheating.

Now, there is no way I would have known he used AI to write his paper, so his telling me was simply to engage me in the conversation. Cheating is defined as "acting dishonestly or unfairly in order to gain advantage" (https://www.dictionary.com/). His grade was far from set, and he took a considerable risk in sharing this information with me, so no, I did not think he was cheating but trying to learn where the boundaries are. When he explained to me how he used ChatGPT 3 (CHAT, https://chat.openai.com/) to write his essay, I was fascinated. I had never heard of this technology before. I had to ask myself some hard questions before I could answer his. It felt like it was one of those pivotal teaching moments where my answer would be weighed heavily so I hedged my answer with a class discussion on the topic that I hoped might give us all a chance to think it through.

The rest of the class was just as interested as I was, but most of them insisted that the student was cheating. They also thought that his actions would rob him of real learning. To prove that he did learn during the process of writing with CHAT, he flawlessly recited the points made in his essay.

Another point the class insisted upon was that work done by artificial intelligence was “not you,” and so not honest. Even though the offending student had a well-thought-out counterpoint to every point they made against it, many held on to their belief that one had to do all the hard work all the time in order to learn, and that anything shy of that was unethical. Many of my colleagues agree. “We have to prepare them for the real world.” I hear them say, but I wonder to which “real” world are they referring? In the real world there are people with divergent communication abilities who are perfectly competent critical thinkers.

Using CHAT could remove barriers for those people and enable them to thrive in business. In the article “Stumbling with their words, some people let AI do the talking” (Harwell et al., 2022), the authors give several examples of how CHAT can be a game changer for those who have been disadvantaged. They reference someone with dyslexia who is worried his words will come out wrong. He fires out a response and then lets AI review it. They say, “AI instantly rewords grammar, deploys the right niceties, and transforms it into a response that is unfailingly professional and polite.” The “real world” is also rife with biases that can easily be worked around using a language model bot. The use of this technology could be an equalizing process for those of us who deal with a world that one could argue is more “real” than it is for others.

The question of intention must come into any consideration of ethics. Not all students come to school because they want to become scholars. Some come because they want to learn tricks of a trade, or to check a to-do box that will improve their chances of employment, or to keep themselves busy and out of trouble while they figure out what they want to do with their lives. English 101 is mandatory for any degree or certificate program but doing the grueling and time-consuming work of unpacking and creating scholarly articles to fully understand the nuances of a topic selected by their instructor may not always be necessary. Getting the gist of a topic through video, quick skims of articles or reading CliffsNotes, can get the job done in a passable way, and I think it’s ok for grown students to choose this. Similarly, using tools like Google, Grammarly, and spell check is widely accepted during the writing process, so I wondered if AI technology is no more or less a tool than those. What is the difference about CHAT that makes it so exciting to the world of technology, and so alarming in the world of academia?

Literature on Artificial Intelligence in the Classroom

Sometimes the most difficult part of research is finding relevant and current literature that addresses the topic of interest. This is not the case with AI. The topic is so groundbreaking that nearly everyone is talking about it in some way. Governments are working out what regulations should be imposed, businesses are determining how to capitalize on AI without compromising reliability, and schools are thinking about the ethics of its uses in the classroom. The general public has already become accustomed to AI in the forms of Siri, Alexa, GPS, Bing, and other apps, but CHAT gives people more control over how and when they might use this emerging technology, and that both excites and frightens everyone involved. The articles and videos we watched and read for the AI unit designed for this study were:

- “The college essay is dead” (2022) by Stephen Marche, which discusses the ethics of using AI in the classroom and the importance of the joining of cultures between humanistic and scientific communities to maintain integrity in business and academia.

- “The surprising thing A.I. engineers will tell you if you let them” (2023) by Ezra Klein, which examines the proposed regulations on A.I. around the world and discusses why A.I. engineers are eager to have regulations in place to slow the pace of progress with this technology.

- “Coded bias” (2021), a documentary by Shalini Kantayya for PBS, explores how technology like face recognition can have bias coded into it. This is applicable to AI in that it, too, is programmed by people who have implicit biases, and this bias can be coded into the programs we engage with.

- “What is ChatGPT? OpenAI’s ChatGPT Explained” (2022), from the YouTube channel How it Happened, which shows a quick history of CHAT and how it works.

Additional articles I made available to the students were:

- “Future of testing in education: Artificial intelligence” (2021), by Laura Jimenez and Ulrich Boser, which examines the benefits and challenges of AI in student learning and how AI can be employed for students’ different learning styles.

- “There is no A.I.” (2023), by Jaron Lanier, which warns that the way to misunderstand and misuse the technology is to mythologize it. AI is a generative mathematical calculation, not a sentient being.

- “When AI chatbots hallucinate” (2023), by Karen Weise and Cade Metz, which explores and explains how and why CHAT so often gets things completely wrong.

METHODS

After logging into CHAT, I entered a series of prompts to obtain a list of media headlines about the developer OpenAI and their software, CHAT. CHAT instantly offered up a list of titles expressing the positive attributes of the technology and how it will better the teaching and learning experience. This surprised me because I had been seeing headlines expressing fear and concerns about the perpetuation of biases, losing our ability to think, and of course, cheating. I asked chat to give me article titles that warn against CHAT and it did so, but its list did not include articles written in the last 2 years, when all the scary information was becoming known. This, I learned, was the first problem with using CHAT in the classroom. It was not up-to-date on the most current information. More than half of the article titles that CHAT provided were not connected to actual articles. Some were close to titles that were published but were not accurate or complete.

With the help of a colleague and a good, old-fashioned library search, I chose 3 of the most current articles available to initiate critical thinking about the topic and used those as the foundation of the 4-week teaching unit I devised for my spring 2023 English 101 classes. I have designed many units in the past, but for this one, I relied heavily on letting CHAT generate the lessons and assignments. I found that creating this teaching unit took a fraction of the time it usually takes, but I also found that the unit created was not terribly interesting, so there was considerable rethinking and tweaking to do before the unit was acceptable. Even still, it did save me a fair amount of time to have CHAT get me started. I found that throughout the process my critical thinking was engaged, my innovative thinking was activated, and the usually grueling process of creating a unit was surprisingly fun to accomplish. In other words, using CHAT to help me do my work was an exciting, thought-provoking, and productive learning experience.

I then presented an introduction to the topic and followed with the video “What is ChatGPT? OpenAI’s ChatGPT Explained” (How it Happened, 2022). Students were asked to complete skeletal notes (partially written notes for students to complete as they read or watch), and then they were given time to discuss their notes with their classmates. Then students were asked if learning about this emerging technology made them curious, anxious, or something else. Students expressed feeling both, with dominant feelings equally divided between curiosity and anxiety. The only variations were that one student said they were “excited,” and one student said they felt “neither.”

The students’ assignments were designed to answer the following questions:

- What exactly is AI?

- How does CHAT work?

- What are the benefits of using CHAT?

- What are the concerns about using CHAT?

- How might academic integrity be affected by CHAT?

- Can students learn while using CHAT, or is it just a task completion exercise?

There were a number of ways I might have approached a unit about AI, but after reading the Stephen Marche (2022) article “The college essay is dead,” I determined that the best approach would be to focus the unit on learning how CHAT is designed to work and what the components of the technology are trained to do. Specifically, I created lessons around what is an algorithm and what are the components of natural-language processing. Marche stated that “The philosophy of language, sociology, history, and ethics are not amusing questions of theoretical speculation anymore.” He suggests that the humanities need to understand natural language processing technology not just “because it is the future of language, but because natural-language processing can throw light on a huge number of scholarly problems.” I wanted to see, and I wanted my students to see that light and understand where the potential problems could be. I discovered that the components of natural language processing were closely related to the English 101 discussions around syntax, semantics, tone, context, and organization, so there are many opportunities to use one for learning the other.

All of the assignments were either designed solely by CHAT after a simple prompt from the instructor, or they were designed by the instructor with some CHAT component to it. An example of an assignment generated entirely by CHAT was a lesson about what an algorithm is. CHAT suggested using a deck of cards to be sorted and categorized into specific steps. An example of an assignment devised by a combination of CHAT and instructor input was the class debate about the benefits and concerns of using AI in a college-level English class. CHAT suggested a classroom debate. The instructor provided the prompt. Students used CHAT to generate debate points, compared responses between groups, and then debated the topic using those responses.

Students were polled at the end of each assignment to determine their satisfaction with the experience. They were also asked to write reflections to answer questions like “What did you learn from that assignment?” and “How clear were the instructions?” or, “How interesting was this assignment to you?” Assignments generated solely by CHAT were rated much less interesting and less clear than those designed by the instructor or by a combination of chat/instructor design. I also obtained written permission by email from 7 students to include their real names and direct quotes throughout this article.

To ensure that students were completing the background assignments, I created skeletal notes for each assigned reading and video. Students completed the skeletal notes before class discussions and used the information to formulate questions to post on the discussion boards. This approach to the readings felt like a CHAT-proof exercise, but students reported that they used CHAT to help them word their questions in a more “academic” way. I posted my own idea,

said Macy Winfield, a first-year student in general studies, but I’m not good at grammar, so I let CHAT reword what I wrote to make it sound more professional.

This quote was reiterated in only slightly different words several times over by other students in the 2 classrooms who claimed that they don’t speak in “a college voice.” This generated an interesting classroom debate about the importance of a unique and authentic voice in writing. In the past, I have tried to have conversations on this topic, but rarely have I observed students being so invested in the discussion as I observed when we were working with the concrete example of CHAT-generated material.

The essay assigned at the end of the unit was created entirely by CHAT with 2 minor adjustments made by me. Those adjustments were the addition of an essential question, and the instruction to include a personal anecdote in the assignment. I thought adding a personal anecdote would force the student to encounter discordant voices within the text, but students worked around it by having CHAT rewrite their anecdote so that it sounded the same as the rest of the essay. Tamar Connely, a first-year student majoring in legal studies, said that he asked CHAT to make up a personal experience for him to write about and that he was fine with that fiction because it was all just an exercise. If the article mattered to me,

he said, I would have put my own story in it.

The students reviewed the completed essays using the same peer review questionnaire that we used for the 2 previous essays with just a few minor adjustments; they were to check the source material for accuracy in context of the quotes, and they were to compare the overall tone of the essay with that of their partner’s essay. The students then revised their essays according to feedback and submitted them for a grade. The consensus was that the drafts generated solely by CHAT were conveyed by Evangeline Tannenbaum as inaccurate, repetitive, and really boring.

The unit’s final assignment was for students to share their insights for the faculty of CCBC to reflect on when trying to create a policy around the use of CHAT in a humanities classroom.

RESULTS

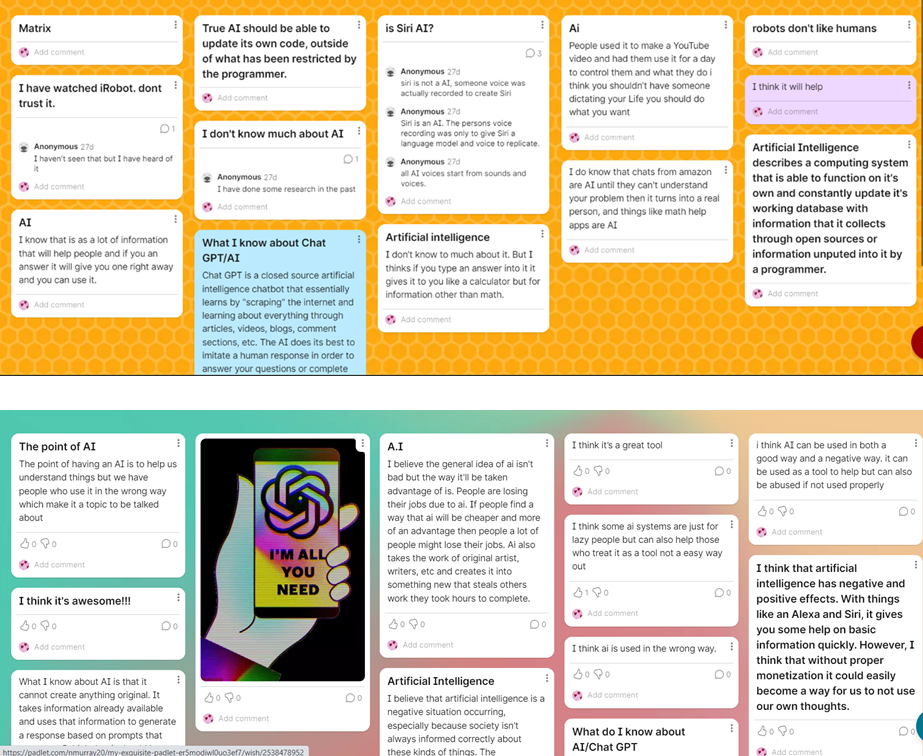

At the start of the unit, I polled the students for their prior understanding about AI. Figure 1 presents screenshots of the students’ responses before and after completing the the unit. The responses students gave before we completed the AI unit are on top. Only 2 students reported hearing of it, with 1 saying he had used it. Most of what the students understood about AI they had learned in science fiction films and social media. At the end of the unit, I polled the students again and the screenshot of those responses are below. By the end of the unit, they understood algorithms, natural-language processing, how bias can be coded into technology, and how to use CHAT to draft an essay.

Student Reflections on CHAT

All 18 students from the 2 English 101 classes were asked to reflect in writing about their experiences and perceptions about CHAT after the unit was completed. Their responses are presented in Table 1.

| Table 1. Pros and Cons of Using AI from written reflections. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pros of AI | Number of reflections that mentioned this | Cons of AI | Number of reflections that mentioned this |

| Students can practice when the teacher is busy. | 11 | Not reliably accurate. | 18 |

| Using outlines/helps organize material. | 13 | Repetitive. | 18 |

| Helps with anxiety about getting started. | 9 | Takes a lot of work to get it to do what you want it to do. | 7 |

| Helps sound more professional. | 17 | Lose your authentic voice. | 5 |

| Learning-divergent students can follow their own thought process in class. | 4 | Can be biased. | 14 |

| Assists to understand complex ideas. | 8 | The work is less creative/enjoyable. | 5 |

I decided to put the contents of Table 1 into a prompt in CHAT and ask it to analyze this survey data for me. Here is the response CHAT gave:

Based on the provided data, here is an analysis of the pros and cons of using AI based on the mentioned reflections:

Pros of AI:

- Students can practice when the teacher is busy. (11 reflections)

- Using outlines helps organize material. (13 reflections)

- Helps with anxiety about getting started. (9 reflections)

- Helps sound more professional. (17 reflections)

- Assists in understanding complex ideas. (8 reflections)

- Learning-divergent students can follow their own thought process in class. (4 reflections)

Cons of AI:

- Not reliably accurate. (18 reflections)

- Repetitive. (18 reflections)

- Takes a lot of work to get it to do what you want it to do. (7 reflections)

- Lose your authentic voice. (5 reflections)

- Can be biased. (14 reflections)

- Can be biased. (14 reflections)

It's important to note that the numbers associated with each reflection represent the frequency of mention in the given survey. These numbers suggest the relative importance or prevalence of each point raised in the reflections. Overall, the reflections highlight several benefits of using AI, including providing practice opportunities, aiding organization, alleviating anxiety, enhancing professionalism, assisting with understanding complex ideas, and catering to diverse learning styles. However, they also raise concerns regarding accuracy, repetitiveness, effort required to customize AI, potential loss of authenticity, bias, and potential impact on creativity and enjoyment. Keep in mind that this analysis is based solely on the provided data, and the specific context and perspectives of the reflections are not considered.

Using CHAT to analyze the data I collected and presented saved me a lot of time. Data analysis is not my strength because the numbers cause me a low-level anxiety that makes processing information more difficult than it should be. Using the technology to process the numbers helped clear the nervousness and gave me a chance to consider the survey results’ meaning. My experience of relief supports the students’ claim that this technology could help students be more successful learners by clearing away the non-cognitive barriers many students face.

Student Reflections on Class Assignments

The students were asked to indicate their impressions on clarity and satisfaction of assignments generated by CHAT and those generated by the instructor, and the results are presented in Table 2. These polls were taken via thumbs up, thumbs down, or thumbs sideways at the end of class. All students were asked to respond, but due to due to respective class attendance the numbers of students reporting for each question vary.

| Table 2. Student Impressions of the Class Assignments. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment / who generated it | Thumbs up (we got a lot out of it and enjoyed it) | Thumbs down (it was confusing and unpleasant) | Thumbs sideways (it was tolerable but not great) |

| Algorithm / CHAT | 0 | 12 | 6 |

| Predictive model / Instructor | 14 | 0 | 2 |

| Debate / both instructor and CHAT | 14 | 0 | 0 |

These results reflect what I personally experienced, which was that CHAT did not generate complete or completely clear instructions. The lessons generated solely by CHAT left the students confused and frustrated. Most CHAT-generated material requires the prompter to think critically and creatively to fill in the gaps to make the assignment satisfactory and successful.

Surprisingly, both classes concluded that CHAT should be allowed as a tool for classwork with only 1 student still unsure. Even those who were adamant in the beginning of the unit that it should be banned from the classroom came to agree that using the technology could make the struggling student’s life much less stressful. It takes away that anxiety of getting started,

said Aniah Bruce, a first-year student studying nursing and initially one of the strongest opponents of using CHAT. I wouldn’t recommend any student use it for the whole thing, but if you are stuck getting started, it really helps a lot with that.

Students also countered the argument that using CHAT would reduce their critical thinking skills by explaining how difficult it was to make CHAT do the work. Tamar said Writing with [CHAT], I took it upon myself to try to remove myself as much as I could from the equation, to say if I wanted to do nothing for this essay at all, I don’t want to do anything, how could I do that effectively and how would that work realistically? What ended up happening was that I had to use [CHAT], and I had to word my questions in the way I wanted it to be written, and I had to engage with my topic by doing that. So, I ended up critically thinking about my topic. I had to engage CHAT to write it properly in a way that I would want it to be written to satisfy my standards. I worked harder on this essay than I did on the others.

When Aniah was asked what she would tell teachers now that she has engaged with CHAT, she said Teachers were concerned about students using [CHAT] because they feel like this will take away from students doing the work, but when using AI, I had to think with CHAT. I still had to use my critical thinking to fully complete the essay, and I had to do my own research, too.

Sha’bria Butler, a sophomore in general studies, also felt there was a considerable amount of work that went into using CHAT but that it was helpful to have CHAT get her started. When we initially had the rough draft in class,

she said, I used CHAT to create an outline and then from the outline whatever it generated like the topic sentences, I used that to make new questions to continually build the paragraphs. Then in the final draft, I put my opinion into it, which was something we talked about in class. [CHAT] is not opinion-based. It gives you, I’m not going to say evidence because some of the work that it displays could be non-fiction. CHAT doesn’t have an opinion, so I had to put my opinion into it. That’s when I created my own topic sentences and built on the paragraphs after I trained AI to do what I wanted it to do.

The students in this study used innovative and critical thought processes to get the job done. The essays did sound different than their natural speaking voices might have, but the material presented was informed by their own thinking.

Christopher Grobe (2023) authored an article for The Chronicle of Higher Education called “Why I’m not scared of ChatGPT” in which he discusses how CHAT has “inspired dark fantasies in the minds of some humanities teachers.” I will admit that it sent a small shudder through my thinking as well, but then I looked at how some universities are welcoming it as a tool for innovation and decided that I would do the same. Grobe suggests that “if we treat learning (not distinction) as the goal of education, then generative AI looks more like an opportunity than a threat.” He acknowledges that, “As software that can simulate human thinking, it may indeed create some thoughtless students who rely on it too heavily. But it might also create students who are ready to think twice, to push beyond statistically likely ways of thinking.” This was certainly my experience. The students who engaged in this experiment with me were not looking for the shortest route to a positive judgement from their instructor, but to really dig in and learn what this emerging technology is all about and what it has to offer. They did not determine that everyone should use it all the time without restriction, but that it should be used as a helpful tool to clarify the ideas that they themselves generate and want to advance.

Even though the students in both classes saw value in using CHAT for tasks to help them get started, organize their thinking, elevate their vocabulary, and generate discussion points, most of them said that they would not want to use it again to draft a whole essay. It’s too hard to get it right, I’d rather just do it my own way and use my own ideas and my own voice

was how Evangeline put it.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In his article “There is no A.I.,” Jaron Lanier (2023) states that “we’re at the beginning of a new technological era—and the easiest way to mismanage a technology is to misunderstand it.” My students have concluded, and I concur, that AI is here to stay, and the best way to make it work for us is to learn to work with it. “Mythologizing the technology only makes it more likely that we’ll fail to operate it well—and this kind of thinking limits our imaginations.” Taking the time to train faculty and then students to first understand the technology and then to use it with intention and caution is the best way forward for academics.

When students were asked to advise faculty about how to proceed, the unanimous opinion was that anyone using CHAT should first make sure they and their students understand what it is and how it works. Knowing that it is trained to fish information from all over the internet and then use that information to predict what to tell us is how we know not to really trust it,

advised Guynan Harrison, a first-year student studying humanities with a focus on creative writing, There is a lot of fake information out there.

They also strongly recommend teaching about the ways a machine can be just as biased as the person who programs it. Finally, they want faculty to create ways for students to use the technology ethically. It’s a tool that can help kids with learning differences,

said Abbey Wilkens, a sophomore who is studying childhood education with special education, but they need to understand the right ways and wrong ways to take advantage of it.

Macy Winfield agrees. Macy is an autistic student. She worked hard in class to get the grade, but it was not because she did not understand the readings. Her neurodiversity makes it difficult for her to put what she knows into words that will satisfy specific audiences. She said that she uses a different app similar to CHAT to help her focus her thinking after she has read and taken notes. Her hard work, she says, earns her the right to do that. Macy wants faculty to make the students earn the privilege of using the shortcut by having them demonstrate an understanding of the fundamental skills. Once they do that,

she said, they’ve earned the right to use whatever tool they want to use.

The students determined that CHAT is an excellent tool that can help with specific tasks that reduce student anxiety around beginning, organizing, and polishing an essay; can support students with divergent learning abilities; can save valuable time when life is overwhelming; but that it is unreliable, repetitive, cumbersome, and unoriginal when put to the task of writing the essay entirely as revealed by the results in Table 1. It was the consensus of both classes that the use of CHAT should be specific to tasks and regulated by the instructors who are fully trained in how the technology works and what the potential issues are before attempting to work with it in the classroom.

What I am taking away from this experience is a strong appreciation for all that CHAT and other natural-language processing models can do to excite, inspire, encourage, and support both faculty and students; but that appreciation is mixed with an equal amount of apprehension. I do not want to caution faculty that students will cheat with CHAT. In my experience, students want to learn. I would caution them that CHAT might cheat the students if they are not armed with a healthy understanding of what they are working with. Guynan noted that we really can’t stop students from using it. It’s already an emerging technology. What’s probably the best course of action to do is to instead learn the technology, understand its pitfalls, where it could potentially benefit, but mostly understanding how it works so we have a better understanding of whether it’s ethical to use. That’s really the core of this conversation.

I agree with her. If it is going to be used as a teaching and learning tool, and let’s face it, it is, then there must be ongoing professional development for faculty to understand what they are working with and how to turn the use of this technology into a productive learning experience for the students. Guynan added that much like it said in one of the articles we read in the class, if we found a way to marry information technology with the humanities there could be a more cohesive way that is more ethical to create work with this technology.

There are indeed many opportunities here to merge humanities with technology in a forward-thinking way, but it cannot be accomplished with limited understanding and fear-based application. Because AI is rapidly improving, faculty and students must work to be up to date with the most recent developments and work together to explore the myriad new possibilities available to them now in the classroom.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to recognize the students who agreed to share their experiences and insights for this article: Tamar Connelly, Guynan Harrison, Abby Wilkens, Sha’bria Butler, Evangeline Tannenbaum, Aniah Bruce, and Macy Winfield were essential contributors to my understanding and to the information presented here.

REFERENCES

- Grobe, C. (2023, January 18). Why I’m not scared of ChatGPT: The limits of the technology are where real writing begins. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-im-not-scared-of-chatgpt

- Harwell, D., Tiku, N., & Oremus W. (2022, December 10). Stumbling with their words, some people let AI do the talking. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/12/10/chatgpt-ai-helps-written-communication/

- How it Happened. (2022). What is ChatGPT? OpenAI's ChatGPT explained [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o5MutYFWsM8

- Jimenez, L., & Boser, U. (2021, September 16). Future of testing in education: Artificial intelligence. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/future-testing-education-artificial-intelligence/

- Kantayya, S. (Director). (2021). Coded bias [Documentary]. PBS; Independent Television Service [ITVS]. https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/documentaries/coded-bias/

- Klein, E. (2023, April 16). The surprising thing A.I. engineers will tell you if you let them. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/16/opinion/this-is-too-important-to-leave-to-microsoft-google-and-facebook.html

- Lanier, J. (2023, April 20). There is no A.I.: There are ways of controlling the new technology but first we have to stop mythologizing it. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/science/annals-of-artificial-intelligence/there-is-no-ai

- Marche, S. (2022, December 6). The college essay is dead: Nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/

- Weise, K., & Metz, C. (2023, May 9). When AI chatbots hallucinate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/01/business/ai-chatbots-hallucination.html